Devarim: The Book that Moses Wrote

While righteous indignation stems from sincere and pure intentions, the highest goals of holiness will only be achieved through calm spirits and mutual respect…

translated by Rabbi Chanan Morrison

Parshat Devarim

Already from its opening sentence, we see that the final book of the Pentateuch is different from the first four. Instead of the usual introductory statement, “God spoke to Moses, saying,” we read:

“These are the words that Moses spoke to all of Israel on the far side of the Jordan River …” (Deut. 1:1)

Unlike the other four books, Deuteronomy is largely a record of speeches that Moses delivered to the people before his death. The Talmud (Megillah 31b) confirms that the prophetic nature of this book is qualitatively different than the others. While the other books of the Torah are a direct transmission of God’s word, Moses said Deuteronomy mipi atzmo — “on his own.“

Unlike the other four books, Deuteronomy is largely a record of speeches that Moses delivered to the people before his death. The Talmud (Megillah 31b) confirms that the prophetic nature of this book is qualitatively different than the others. While the other books of the Torah are a direct transmission of God’s word, Moses said Deuteronomy mipi atzmo — “on his own.“However, we cannot take this statement — that Deuteronomy consists of Moses’ own words — at face value. Moses could not have literally composed this book on his own, for the Sages taught that a prophet is not allowed to say in God’s name what he did not hear from God (Shabbat 104a). So what does it mean that Moses wrote Deuteronomy mipi atzmo? In what way does this book differ from the previous four books of the Pentateuch?

Tadir versus Mekudash

The distinction between different levels of prophecy may be clarified by examining a Talmudic discussion in Zevachim 90b. The Talmud asks the following question: if we have before us two activities, one of which is holier (mekudash), but the second is more prevalent (tadir), which one should we perform first? The Sages concluded that the more prevalent activity takes precedence over the holier one, and should be discharged first.

One might infer from this ruling that the quality of prevalence is more important, and for this reason the more common activity is performed first. In fact, the exact opposite is true. If something is rare, this indicates that it belongs to a very high level of holiness — so high, in fact, that our limited world does not merit benefiting from this exceptional holiness on a permanent basis. Why then does the more common event take precedence? This is in recognition that we live in an imperfect world. We are naturally more receptive to and influenced by a lesser, more sustainable sanctity. In the future, however, the higher, transitory holiness will come first.

The First and Second Luchot

This distinction between mekudash and tadir illustrates the difference between the first and second set of luchot (tablets) that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai. The first tablets were holier, a reflection of the singular unity of the Jewish people at that point in history. As the Midrash comments on Exodus 19:2, “The people encamped — as one person, with one heart — opposite the mountain” (Mechilta; Rashi ad loc).

After the sin of the Golden Calf, however, the Jewish people no longer deserved the special holiness of the first tablets. Tragically, the first luchot had to be broken; otherwise, the Jewish people would have warranted destruction. With the holy tablets shattered, the special unity of Israel also departed. This unity was later partially restored with the second covenant that they accepted upon themselves while encamped across the Jordan River on the plains of Moab. (The Hebrew name for this location, “Arvot Moav“, comes from the word arvut, meaning mutual responsibility.)

The exceptional holiness of the first tablets, and the special unity of the people at Mount Sinai, were simply too holy to maintain over time. They were replaced by less holy but more attainable substitutes — the second set of tablets, and the covenant at Arvot Moav.

Moses and the Other Prophets

After the sin of the Golden Calf, God offered to rebuild the Jewish people solely from Moses. Moses was unsullied by the sin of the Golden Calf; he still belonged to the transient realm of elevated holiness. Nonetheless, Moses rejected God’s offer. He decided to include himself within the constant holiness of Israel. This is the meaning of the Talmudic statement that Moses wrote Deuteronomy “on his own.” On his own accord, Moses decided to join the spiritual level of the Jewish people, and help prepare the people for the more sustainable holiness through the renewed covenant of “Arvot Moav“.

Moses consciously limited the prophetic level of Deuteronomy so that it would correspond to that of other prophets. He withdrew from his unique prophetic status, a state where “No other prophet arose in Israel like Moses” (Deut. 34:10). With the book of Deuteronomy, he initiated the lower but more constant form of prophecy that would suit future generations. He led the way for the other prophets, and fortold that “God will establish for you a prophet from your midst like me” (Deut. 18:15).

In the future, however, the first set of tablets, which now appear to be broken, will be restored. The Jewish people will be ready for a higher, loftier holiness, and the mekudash will take precedent over the tadir. For this reason, the Holy Ark held both sets of tablets; each set was kept for its appropriate time.

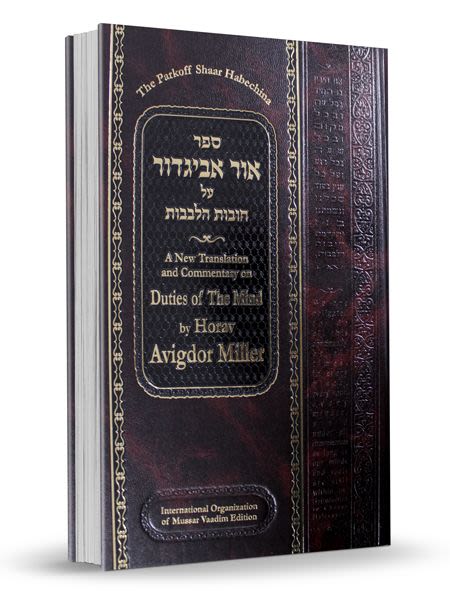

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 287-290. Adapted from Shemuot HaRe’iyah, Devarim (1929))

Rabbi Chanan Morrison of Mitzpeh Yericho runs http://ravkookTorah.org, a website dedicated to presenting the Torah commentary of Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaCohen Kook, first Chief Rabbi of Eretz Yisrael, to the English-speaking community. He is also the author of Gold from the Land of Israel (Urim Publications, 2006).

Tell us what you think!

Thank you for your comment!

It will be published after approval by the Editor.