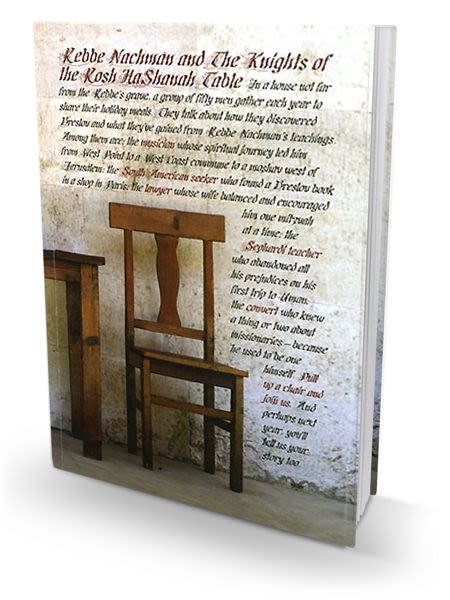

The Rebbe’s Rosh Hashanah

Rebbe Nachman once declared: "…My entire mission is Rosh Hashanah." He was particularly emphatic about his...

Historical Overview

Rebbe Nachman once declared: “Gohr mein zach is Rosh Hashanah . . . My entire mission is Rosh Hashanah.” He was particularly emphatic about his followers coming to him for Rosh Hashanah, and indicated on his last Rosh Hashanah in Uman that we should continue to do so even after his death (Chayei Moharan 403-406; Likkutei Moharan I, 211; ibid. II, 94; Kuntres “Ha-Rosh Hashanah Sheli,” citing numerous additional sources).

There is a Breslover saying: Everyone declares “Ha-Melekh” on Rosh Hashanah − but the coronation is in Uman! (Rabbi Shmuel Horowitz, Tzion ha-Metzuyenes, Hakdamah).

Reb Avraham Sternhartz had a tradition that Reb Nosson once remarked, “Even if the road to Uman were paved with knives, I would crawl there − just to be with Rebbe Nachman for Rosh Hashanah.” This is also cited by Reb Avraham ben Nachman Chazan (Tovos Zichronos, p. 137; cf. Kokhvei Ohr, Anshei Moharan, 3 [Jerusalem 1983 ed.] p. 69).

Reb Nosson also said, “Whoever comes to Rebbe Nachman’s burial place in Uman for Rosh Hashanah has a share in bringing the Redemption” (Kokhvei Ohr, Anshei Moharan, 4 [Jerusalem 1983 ed.] p. 69).

The Rebbe once told his followers: “Whether you eat or you don’t eat, whether you sleep or you don’t sleep, whether you daven [with proper concentration] or you don’t daven − just make sure that you are with me for Rosh Hashanah!” (Chayei Moharan 404).

Rebbe Nachman promised: “I have already looked after the traveling expenses of my people who come to me for Rosh Hashanah − and also their expenses for the return trip.” He also added, “Bie mir, hott nokh keiner nisht derlaygt . . . With me, nobody has lost out yet!”(Cf. Si’ach Sarfei Kodesh II, 27, 28).

In 1929, when the borders between Poland and the Ukraine were closed, the Breslover Chassidim of Poland wrote to Rabbi Shimshon Barsky in Uman, asking if they could establish their own kibbutz, or gathering for Rosh Hashanah. Reb Shimshon told them that he would consult Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz on this important question. Eventually the two Breslover elders assented to the establishment of a Breslover kibbutz in Lublin for Rosh Hashanah, which for a time was hosted by Rabbi Meir Shapiro in the Chakhmei Lublin Yeshiva. However, this gathering was meant as a temporary measure, not as a substitute for going to Uman. “The Rebbe’s Rosh Hashanah is only in Uman,” they cautioned. With these words, Reb Shimshon and Reb Avraham reiterated the central importance of going specifically to the tzaddik on Rosh Hashanah. Yet the Lubliner kibbutz became a precedent for other such Breslov gatherings in the decades to come, when the “Iron Curtain” closed on Uman and the Ukraine (See She’aris Yisrael, Mikhtav 62).

From the mid-1930s until the late 1980s, it was virtually impossible to travel to Uman (with only a few rare exceptions to this rule). Therefore, Breslover Chassidim would gather in various core communities in order to pray together on Rosh Hashanah and not forget the ‘inyan of “The Rebbe’s Rosh Hashanah” entirely. As time passed, some well meaning individuals in Eretz Yisrael developed the rationale that it was enough to pray with other Breslover Chassidim on Rosh Hashanah. They felt that the Breslover kibbutz in Yerushalayim had effectively replaced Uman. They justified this by arguing that the kibbutz need only be in a shul that was nikra al shemo, i.e. it bore the Rebbe’s name.

Others misinterpreted certain statements in Breslover seforim about reciting Tikkun haKlali, etc., near the grave of the tzaddik on Erev Rosh Hashanah, taking these remarks to mean that being with the tzaddik on Erev Rosh Hashanah was the main thing. However, Reb Avraham had brought proofs that a Breslover Chassid must actually go to the tzaddik in order to be with him on Rosh Hashanah, and everything else is secondary. The question was: if one cannot go to Uman, is there any alternative?

Beginning in the late 1930s, when Reb Avraham Sternhartz came to Eretz Yisrael, he and his initial group of talmidim began to travel to Meron for Rosh Hashanah, in order to pray near the grave of the holy Tanna and author of the Zohar, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. Given the deep connection between the Rebbe and Reb Shimon, which pervades all of Breslov literature, Reb Avraham understood that one who cannot go to Uman to be with the Rebbe should go to Meron. To be sure, Reb Shimon is called the “tzaddik yesod ‘olam.” Moreover, based on numerous mesorahs from Reb Noson’s talmidim, it was Reb Avraham’s conviction that through Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai one may spiritually bind himself to the Rebbe and his tikkunim.

(These ideas are presented by Reb Avraham in his Kuntres “Imros Tehoros,” printed together with his oral traditions, Tovos Zichronos, and formalized by Rabbi Shmuel Moshe Kramer of Jerusalem, Kuntres “Chadi Rabbi Shimon.” This work provides a number of historical precedents for Breslover Chassidim going to Reb Shimon on Rosh Hashanah; also see Si’ach Sarfei Kodesh I, 234, “Ksav Yad ha-Rav mi-Tcherin,” regarding the connection between Rabbi Shimon and Rebbe Nachman. Reb Avraham ben Nachman states: “Our entire hope for the imminent Final Redemption in these times, which are the “heels of the Mashiach,” is through the tikkunim of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and the Rebbe, of blessed memory, which they accomplished on the day of their passing from the world.” He also states: “Through our rejoicing and our love and our unity as a result of our connection to the soul of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai − through this specifically we derive the ability to draw and receive from the ‘Nachal Novea’ [“Flowing Brook,” a euphemism for the Rebbe]…” cited in Chadi Rabbi Shimon, p. 4.)

Rabbi Elazar Kenig pointed out that because of Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz’s clear da’at, the ‘inyan of traveling specifically to the tzaddik was not lost. After Rabbi Sternhart’z passing, Rabbi Gedaliah Kenig and Reb Avraham’s other talmidim carried on his legacy by continuing to travel to Meron for Rosh Hashanah. They did so with tremendous self sacrifice, and did not exchange the ‘inyan of kibbutz, which is secondary, with the ‘inyan of tzaddik, which is primary.

Many decades later during the late 1980s, through Hashem’s great kindness, it again became possible to travel to the Rebbe’s tziyun. The same questions were still a source of heated debate. Not everyone initially agreed that the ‘olam should travel from Eretz Yisrael and all points on the globe in order to be in Uman on Rosh Hashanah. However, eventually these confusions and ideological conflicts subsided, and today the Uman gathering is bigger than ever.

Unsure if he would be able to go to Uman or Meron, someone from Brooklyn, NY, once asked Reb Elazar Kenig if it would be better to pray on Rosh Hashanah with a living tzaddik, such as another Chassidic Rebbe, or if he should daven with the local Breslov minyan. Rav Kenig replied that if one were prevented from going to Uman or Meron, God forbid, it would be better to daven in a local Breslov minyan on Rosh Hashanah. At least this is an expression of the desire to go to the Rebbe for Rosh Hashanah. Yet a committed Breslover should not opt for this except when there is no other choice.

Erev Rosh Hashanah

One should arrive well before the selichot of Erev Rosh Hashanah (“Zekhor Bris”), and leave soon after Rosh Hashanah. “Zekhor Bris” is an important part of the preparation for Rosh Hashanah. This reflects the drawing forth of illumination preliminary to the revelation of the light itself, a concept that pervades the writings of the ARI zal.

In Uman, the lengthy selichot of “Zekhor Bris” begin at 3:00 AM. Many immerse in a mikveh prior to this. Following the conclusion of selichot, one washes one’s hands for Shacharit, and then davens at sunrise. After Shacharit most of the ‘olam performs hatorat nedorim (annulment of vows).

If one has the strength, it is proper to fast on Erev Rosh Hashanah. However, most Breslovers do so only until noon (Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chaim 581:2; Kokhvei Ohr, Anshei Moharan, “Yesodos ha-‘Ikkariyim,” 34 [p. 79]; cf. Si’ach Sarfei Kodesh II, 565).

It is customary to recite Tikkun Haklali on Erev Rosh Hashanah, preferably beside Rebbe Nachman’s grave site. It is beneficial to do so even if one is not in Uman.

Once, on Erev Rosh Hashanah in the morning, Reb Nosson’s son, Reb Yitzchok, was not well and asked his father if he could eat something before going to the Rebbe’s tziyun, so that he would have the strength to express himself more fervently. Reb Nosson told Reb Yitzchok that he should do the best he could − as long as it was before breaking his fast (See Kokhvei Ohr, Anshei Moharan, “Yesodos ha-‘Ikkariyim,” 33 (p. 79); cf. Si’ach Sarfei Kodesh II, 565, for a slightly different version of this oral tradition).

On Erev Rosh Hashanah, one should go to the Rebbe’s tziyun (or in Meron to the tziyun of Reb Shimon) to recite vidu’i devarim/confession of sins. There was a period when the Chassidim did so in the Rebbe’s presence. However, the Rebbe eventually curtailed this practice. Today one recites the confession verbally, but in private. One should try to detail one’s sins and transgressions, going back as far as one can remember, asking Hashem for forgiveness and the chance to make a fresh start in life.

On Erev Rosh Hashanah when the Rebbe was alive, the Chassidim recited vidu’I devarim/confession of sins in his presence. Today, too, one does so at the Rebbe’s tziyun, in keeping with the principle that “the tzaddikim after death are called ‘living’ (Berakhos 18a). One should recite the confession verbally (although not audibly to others), trying to detail one’s sins and transgressions as far back as one can remember, and ask Hashem for forgiveness and the chance to make a fresh start in life. As a result of this ‘avodah, one may hope and be assured that the Rebbe, like a living teacher, will guide him along the correct path of teshuvah, each person according to the root of his soul. (Confession is a basic part of teshuvah; see Yoma 35b-37a; Mishneh Torah, Hilchos Teshuvah 1:1-2, et al. The tikkun of vidu’i devarim in the presence of a tzaddik is discussed in Likkutei Moharan I, 4. There it states that the tzaddik who has attained total self-nullification like Moshe Rabbenu (Moses) can bring about the cleansing of sin.

The Tcheriner Rav, Parpara’os le-Chokhmah, ad loc., mentions the custom of reciting vidu’i at the Rebbe’s tziyun. However, this ‘avodah is not limited to Erev Rosh Hashanah and Uman. One who cannot go to the Rebbe’s tziyun may also be privy to this tikkun by reciting confession be-hiskashrus to the tzaddik; see Likkutei Tefilos I, 4 [in more recent editions, subsection 32, et passim].)

Someone once asked Reb Elazar Kenig about the origin of the custom to remove one’s leather shoes when standing near the grave of a tzaddik. Reb Elazar explained that this is an expression of yirah (reverence). The Torah states that when Moshe Rabbeinu drew near to the sneh (Burning Bush), he was told to remove his shoes. This is evidently the source of this custom, which is followed by many Russian and Ukrainian Chassidim, including those of Chernobyl, Skver, Lubavitch, and Karlin-Stolin. It may have once been followed by Breslover Chassidim, as well. However, if we once had such a mesorah, it seems to have been lost. Moreover, the area surrounding the Rebbe’s tziyun no longer has the status of a cemetery, and in recent years a shul has been built next to it. People wear their shoes there, as in any public place. Therefore, when the questioner asked if one should remove his shoes at the Rebbe’s tziyun, Reb Elazar answered in the negative, adding that as a rule, one should not do things that look strange to other people. Yet we should have the same yirah that lies at the root of this minhag.

Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz used to recite Likkutei Tefillos, Tefillah 13, on Erev Rosh Hashanah. (This tefillah is based on Likkutei Moharan I, 13, one of the Rebbe’s major Rosh Hashanah lessons.)

Rebbe Nachman said than on Erev Rosh Hashanah, one should give a pidyon nefesh, an unspecified amount of tzedakah appropriate to the individual’s financial circumstances.

The main rule in determining how much to give is that minimally it should be an amount that one feels is significant − that is, one should feel the “pinch.” For one person, this may be $5, for another, $5,000. It is also proper to write a kvittel with one’s name and mother’s name, as well as those of family members and others. In the Rebbe’s day, the pidyon nefesh was given to him personally. Today it is given to a Breslover elder or teacher. As in most Chassidic circles, it is customary to write the kvittel on plain white paper. (See Sichos ha-Ran 214)

Rosh Hashanah

It is a Yerushalmi custom to wear a white caftan on Rosh Hashanah, both by day and by night. In recent years, this has also become the prevailing Breslover custom in Uman and Meron. Those who do not wear a Yerushalmi caftan commonly wear a regular kittel, as on Yom Kippur. However, Breslover Chassidim of previous generations did not wear a white caftan or kittel on Rosh Hashanah.

It is an old Breslover custom for everyone to clap when the shaliach tzibbur (Cantor) intones “Ha-Melekh” toward the end of Pesukei de-Zimra, at the end of “Keter Melukhah,” and at a few other points in the service. This is an expression of our joy at participating in the “coronation” of Hashem (so to speak).

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Bender states that on Rosh Hashanah and during the ‘Aseret Yemei Teshuvah in Uman, the Shir ha-Ma’alot after Yishtabach was recited all at once, not responsively verse by verse. This was a regional minhag, which is still observed by Skverer Chassidim, among others. Similarly, after Ma’ariv during the Yomim Nora’im, it was customary to recite Li-Dovid Mizmor all at once, not verse by verse. However, today in Uman and Meron both psalms are recited verse by verse, as in most communities. (Si’ach Sarfei Kodesh IV, 230)

On the Yomim Nora’im, the ARI zal would say the piyyutim in Birkhas Kri’as Shema’, while the Baal Shem Tov would not. The Breslov community takes an in-between position, reciting some of them. However, more piyyutim are recited in this part of the service on Yom Kippur than on Rosh Hashanah (Re. the ARI zal and Baal Shem Tov, see Shulchan ha-Tahor [Komarno] 68, s.k. 1-2).

In the passage from Shemoneh Esreh that begins “U-vekhein tein pachdekha,” the ARI zal omitted the word “ki’mo” that precedes “sheyad’anu.” However, in Uman and Meron, the minhag followed by the shaliach tzibbur is to say the word “ki’mo,” as printed in most machzorim.

(For the view of the ARI zal, see Rabbi Chaim Vital, Sha’ar ha-Kavannos, Drushei Rosh Hashanah, Drush 6. The nusach “kimo” is supported by Tur, Machzor Vitry; also see Likkutei MaHaRiCH III, p. 612.)

The minhag followed by the shaliach tzibbur in Uman and Meron is to say “ki-‘ashan,” not “bi-‘ashan,” during the Shemoneh Esreh. (Siddur Rav ‘Amram Gaon; Kol Bo; MaHaRiL; Matteh Moshe; Siddur ha-RaMaK; Minhagei ha-GRA; Shulchan ha-Tahor−Komarno; Siddur Magen Avraham−Slonim; et al. Alternatively, the nusach “bi-‘ashan,” based on Tehillim 37:20, is supported by Abudarham, Siddur ha-Ya’avetz; Pri Chadash; Siddur ha-Rav Baal ha-Tanya; Siddur Tefillah Yesharah−Berditchev; Chayei Adam 139:3; Matteh Ephraim; Ru’ach Chaim; Siddur Kavannos ha-RaSHaSH; et al. This is one of the rare instances in which Rabbi Chaim Elazar Spira of Munkatch resorts to a double expression, saying both “bi-‘ashan” and “ki-‘ashan”; see Darkhei Chaim vi-Shalom, Rosh Hashanah 711, ff. 10; also Likkutei MaHaRiCH III, p. 613.)

Rebbe Nachman said that one should limit one’s speech on Rosh Hashanah. Therefore, it is proper to refrain from small talk, and concentrate on words of Torah and tefillah, each person according to his ability. Many Breslover Chassidim do not engage in any casual speech at all on the first night, when the heavenly judgment is most severe. Some maintain silence until the second day after Musaf. Still others restrict themselves until the end of Rosh Hashanah. In any case, one should be extremely careful in matters of speech on Rosh Hashanah, as well as at all times (See Sichos ha-Ran 21).

The Rebbe taught that by traveling to the tzaddik for Rosh Hashanah, the “head of the year,” we could attain purification of the mind. This, too, mitigates harsh judgments. However, he added, we must use wisdom on Rosh Hashanah and think positive thoughts − for what we think about on Rosh Hashanah is potent (Likkutei Moharan I, 211; Sichos ha-Ran 21).

In keeping with the minhag presented in the Shulchan Arukh, Breslover Chassidim are accustomed to say a “yehi ratzon” on various simanim tovim at the beginning of the meal, as stated in the machzor (Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chaim 583:1; also see Darkei Moshe, ad loc., citing Maharil; Abudarham, Seder Arvis shel Rosh Hashanah, pp. 265-266. The Gemara mentions this custom in Horayos 12a and Kerisos 6a.)

Prior to the other simanim, one dips a slice of apple in honey and asks Hashem for a “shanah tovah u-metukah,” a good and sweet year. The “yehi ratzon” is recited after tasting the apple, to avoid a hefsek —interruption between the blessing and eating(Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chaim 583:1, RaMaH; Mishnah Berurah, ad loc., s.k. 3. This is the prevailing custom in most communities today. However, cf. Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, Shulchan Arukh ha-Rav, Orach Chaim III-IV, Hosafos: Kiddush le-Rosh Hashanah, that the custom of Chabad is to recite the “yehi ratzon” after the berakhah but before tasting the fruit. A precedent for this may be found in the commentary on the machzor, Ma’agley Tzedek, which cites this as the common minhag in sixteenth century Poland, White Russia, and Lithuania.)

After reciting “ha-motzi,” one also dips the challah in honey, beginning on the first night of Rosh Hashanah and continuing until the end of Sukkos. Reb Elazar dips the challah first in salt and then in honey (Ibid).

It is the Breslov custom to recite tashlich at the end of the first day of Rosh Hashanah (if possible), not later during the ‘Aseret Yemei Teshuvah. The ARI zal states that one should preferably perform tashlich on the outskirts of town. The Rebbe used to go to the Bug River in Breslov. In Meron, Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz used to walk down the steep hill from the synagogue atop Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai’s grave to Megiddo. Once he could not walk back up the hill, so one of the younger men carried him on his shoulders. On another occasion, Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz stopped part of the way, and delivered his Rosh Hashanah lesson from Likkutei Moharan by heart, right then and there (Re. the ARI zal, see Rabbi Chaim Vital, Sha’ar ha-Kavannos, Drushei Rosh Hashanah, 90b).

In Uman, tashlich is recited beside the reservoir down the hill from the Kloiz. The entire body of water is surrounded by many thousands of Chassidim. In previous generations, it was not customary to sing or dance after tashlich. However, today the joy of being part of the “Rebbe’s Rosh Hashanah” is irrepressible, and many Chassidim do so.

On the second night of Rosh Hashanah following tashlich, it is customary for various Breslover teachers to give shiurim in Likkutei Moharan. This is when the Rebbe delivered his Rosh Hashanah lesson every year.

After the conclusion of Ma’ariv of Motza’ei Rosh Hashanah, the Chassidim join hands and dance. This rikkud usually concludes with the Yiddish song: “Tirer brieder, hartziger brieder, ven veht men zich vieter zehn? Ven veht men zich vieder zehn? Az Gott veht geb’n gezundt un lebben − veht men zich vieter zehn . . . Dear brothers, beloved brothers, when will we see each other for longer? When will we see each other again? When God will give health and life − then we will see each other again!”

***

Used with permission from the Nachal Novea Mekor Chochma

Tell us what you think!

Thank you for your comment!

It will be published after approval by the Editor.