Journey to Uman – Rosh Hashanah 1997

The obstacles are an important part of the journey -- they are really spiritual tests to see how sincere you are about going. Read one pilgrim's journey during the early years...

My pilgrimage to Uman really began in the mid-1970’s, when I first read Rebbe Nachman’s promise to be a heavenly advocate for anyone who would make this journey:

Whoever comes to my grave site [in Uman, Ukraine] recites the Ten Psalms of the Tikkun K’lali (General Remedy), and gives even as little as a penny to charity for my sake, then, no matter how serious his sins may be, I will do everything in my power — spanning the length and breadth of Creation — to cleanse and protect him. By his very payot (sidecurls) I will pull him out of Gehenna (purgatory)! (Rebbe Nachman’s Wisdom #141).

“By his very payot I will pull him out of Gehenna!” the Rebbe said. I really took that to heart. For many years I have joked that this is why I have such long sidecurls — because when my time comes after 120 years, I want the Rebbe to be able to get a good grip!

But on the serious side, Gehenna does not have to be a hellish place somewhere in the afterlife — it can also be experienced right here on earth. My life up to that point had been hellish indeed, and there were many problems in my own personal Gehenna that I could not seem to overcome. Something about the Rebbe’s promise deeply touched my heart, and set me on a course which led me to Uman in 1997. So my pilgrimage really did begin on that day over two decades ago, when I first longed to make the journey.

A bit of history….

Who was Rebbe Nachman? He was the great-grandson of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, better known as the Baal Shem Tov (Master of the Good Name), founder of Chassidism. Rebbi Nachman was born in 1772 in what is now the Ukrainian Republic, and in the founder of the Breslov Hasidic movement. Unfortunately, he contracted tuberculosis at a time when there was no cure, and died of this disease in 1810, at the young age of 38. A few months before his death, he expressed the desire to be buried in Uman, among the thousands of Jews who had been martyred there. Rebbe Nachman passed away on the fourth day of Sukkot, October 16, 1810, and, according to his instructions, was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Uman, Ukraine.

The first pilgrimage to the grave site was led by his chief disciple, Reb Nosson, in the spring of 1811. From that point on, it became customary for Breslover Hasidim to try to make the journey at least once in their lifetime. Although this pilgrimage could be made at any time of the year, the main gathering was always at Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year). “Uman, Uman, Rosh Hashanah!” became the rallying cry for Breslevers to gather on this holy day.

However, at the time I heard about Uman in the 1970’s, Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, and the Cold War was in full force. It was almost impossible for anyone to make a pilgrimage to Uman. I say “almost impossible,” because a few Breslover Hasidim did manage to get to Uman during the Communist regime — at great expense and risk to themselves. Back then, it was necessary to travel all the way to Kiev just to apply for a visa — and one was as likely as not to be refused. Even if a visa was granted, it was only to go there and back in a single day. To stay overnight in Uman — and especially for Rosh Hashanah — was not permitted by the Soviet authorities. And so, for me, traveling to Uman remained but a dream.

After the fall of Communism

In 1989, with the fall of Communism, the possibility opened up for Breslevers to once again openly travel to Uman. I first heard about this while spending Rosh Hashanah with a Breslov community in Brooklyn that same year. For over a decade I had been reading whatever I could find about Rebbe Nachman, and felt a very close personal relationship to his spirit. But, because I lived in the Midwest where there are no Breslov communities, and because I had very little money for personal travel, I had never had any contact with the present-day community.

Then in 1989, because of a speaking engagement on the East Coast the previous week, it was possible for me to spend Rosh Hashanah with Breslover Hasidim in New York. This was all the more exciting to me because, at the time I had first heard of Rebbe Nachman in the 1970’s, I was not even sure that there were still Breslov communities around. During the Nazi time, over 14,000 Jews were deported from Uman to the camps. The hauntingly beautiful tune to Ani Maamin (“I Believe”), which we now associate with the Holocaust, is attributed to Breslov, and was sung in obedience to Rebbe Nachman’s teaching to “Never despair! Never give up hope!” But by the end of World War II, less than 150 Breslevers had survived. So it took a few decades for the community to recover and begin doing outreach again.

I returned home from Brooklyn filled with joy and more certain than ever that Breslov was indeed my path, and that Rebbe Nachman was my Rebbe. I tried, as best as I could, to follow his teachings, especially by making hitbodedut (personal private prayer) which I had already been doing since childhood, long before I ever heard of it as a “Breslov” teaching. Now I took it on with greater intensity as a daily spiritual practice.

I also began to recite the Ten Psalms (16, 32, 41, 42, 59, 77, 90, 105, 137, and 150 in that order) recommended by the Rebbe for his Tikkun HaK’lali (General Remedy). While in Brooklyn I had learned that Breslevers try to recite them every day, not just at the Rebbe’s grave. So I began to do the same — mostly in English, since I am dyslexic and my Hebrew-reading skills are rather weak. But I knew a nice, happy tune to Psalm 150, so it became my personal practice to end my recitation by singing that Psalm in Hebrew and, if nobody else was looking, to even dance around a bit. This practice sustained me through many a crisis!

I also continued to study the Rebbe’s writings, which meant reading the same few books over and over again, because Breslov materials were difficult to find in Minnesota. Then came the Internet — and with it, access to a lot of people and resources. Now, at last, I could be in regular contact with Hasidim who actually practiced this path. From then on, as I traveled around the country in connection with my work, I tried to stay with Breslevers whenever possible. Although, these encounters were few and far between, they greatly strengthened my commitment to the Rebbe’s way.

An invitation to Berlin

Next came my trip to Germany in April 1997. I had been invited to Berlin for a conference on “Reincarnation and Karma,” to speak about my two books on cases of reincarnation from the Holocaust. This would be my first trip to Europe and, when I mentioned it to Ozer Bergman (a Breslov internet friend), he immediately suggested that I should try to make a side trip to Uman. Great idea — but my schedule was so tight for that trip that it just did not work out. How frustrating, to be so near and yet so far!

It is a Breslov axiom that as soon as one makes the commitment to go to Uman (or do any other good deed), obstacles arise from the yetzer hara (side of negativity) which try to stop you. It is also a Breslov axiom that one should never give up or allow these obstacles to get in the way of achieving the goal. The obstacles are really tests which the yetzer hara throws up to try to discourage us from doing mitzvot (commandments, good deeds.) The more holy the activity, the bigger the stumbling blocks that the yetzer hara puts in the way. So when these obstacles come up, it is a sure sign that you are on the right track — and must forge ever onward at all costs.

Reb Nosson, Rebbe Nachman’s closest disciple, once said, Even if the road to Uman were paved with knives, I would crawl there — just so I could be with my Rebbe on Rosh Hashanah! (Tovot Zichronot p. 137).

Luckily, I did not have to crawl over a trail of knives, thank heavens! While in Berlin, I learned that a Dutch translation of my book Beyond the Ashes would be coming out in the fall of that same year. The Dutch publisher asked if it would be possible for me to come back to Europe in mid-September, to attend a multi-cultural conference in Bad Gandersheim, Germany, and also promote the book in Amsterdam. The publisher would pay my travel expenses and the German conference would pay an honorarium.

When I looked at my calendar there in Berlin, I could hardly believe my eyes — that trip would get me to Europe two weeks before Rosh Hashanah! The real miracle was the perfect timing. In most years, Rosh Hashanah is already over by mid-September. But in 5758 (1997) Rosh Hashanah came very late, beginning on the evening of October 1. If I went to Holland and Germany, I would have two weeks to somehow get myself to Uman. So of course, I said “yes” to the invitation! And once I made that commitment, a series of events led to many people helping me get to “the Rebbe’s Zion” in Uman.

Overcoming obstacles

But there were also serious obstacles to overcome — obstacles that I shall describe in some detail here, in order to show how everything worked out in the end, and thereby give courage to others who may want to make the trip. The obstacles are an important part of the journey — they are really spiritual tests to see how sincere you are about going. In my case, I believe these tests played a big part in cleansing my heart and preparing me for arrival in Uman.

But back to my story: I now had a way to get to Europe, which was a major breakthrough. But I still faced the challenge of getting a visa to Ukraine. Nowadays you do not have to go all the way to Kiev first, but there is still a lot of red tape, and the rules change all the time, so what I’m about to describe may be obsolete tomorrow. As of this writing, one cannot simply show up at the border as a tourist — I had to have an invitation from a Ukrainian citizen or group in advance, and I had to send my passport to the Ukrainian embassy in New York City in advance. I also had to pay $95 for the visa. All this can — and should — be arranged through a travel agent — in my case, a Breslover named Shlomo Fried of Nesia Travel in in New York, who was most helpful in cutting the red tape.

However, there was a major obstacle at one point when the Ukrainian embassy was telling us that we would all have to pay in advance for hotel rooms in Kiev — an outrageous demand, since we were not staying in Kiev, and there are no hotels in Uman! (We’ll get to the housing arrangements later.) I could barely afford the trip itself, and paying for useless hotel rooms was out of the question. If they insisted on this, I might not be able to go…

Things were getting down to the bottom line, because it was already mid-July, and I was leaving for Europe on September 7th. I was seriously worried that not only would I not get a visa, if I sent my passport to the embassy in New York and there was a delay, I might not get it back in time to go to Europe at all. So I spent many intensive hours in hitbodedut, walking in the woods by our farm and talking to God about this, begging, pleading for things to work out. And — miracle of miracles! — the embassy suddenly removed the demand for prepaid hotel rooms, and I was able to get a visa.

Meanwhile, the United Parcel Service had gone on strike, so I could not simply trot down to the UPS office in my town to send my passport off to New York. I would have to send it by Federal Express, and the nearest Fed-Ex office was in Duluth, 65 miles away. Because of the overload of business from the UPS strike, the Fed-Ex people were not picking up packages – they had to be brought to the office. That meant a special last-minute trip to drive to Duluth, send the passport by express, and hope that it would not get lost in the huge backlog. I prayed a lot that night!

In a little over a week I had my passport back, along with my visa. In the meantime, I had been investigating various possibilities for flights from Europe to Kiev. Unfortunately, I was about 2000 frequent flyer miles short from having a free ticket from KLM Airlines out of Amsterdam. So I decided to meet up with a Breslov group leaving from Paris. The cost was $460 (including the bus from Kiev to Uman and back), and by a “coincidence” I had just gotten $500 from a speaking engagement in Washington DC. I was about to send in this money for the plane reservation, when a very generous person — may he be forever blessed! — decided that, since he could not go to Uman himself, he would help me get there donating $500! That paid for the plane ticket and freed up money for other expenses. As it turned out, I did need that extra money because of even more obstacles…

Surviving in Europe on less than a shoestring

Next, I had to figure out what I was going to do for two weeks in Europe between the end of the conference in Germany and the time my plane left Paris on September 30th. I am not a rich man, and was traveling on less than a shoestring, so spending two weeks in hotel rooms was out of the question. There are those who would say it is sheer folly to go to a foreign country with so little cash in hand. In practical terms, they are right — but when it comes to Uman, who is being practical?

I had assumed I could get some more speaking engagements in Europe to cover the travel costs, but the timing was all wrong, and nothing seemed to be working out, except for the original invitation to the German conference. Even that had its moments of panic, because when I got there, I found out that there had been a big misunderstanding about my honorarium, and the money was not at the conference. I had been counting on that money for my living expenses, and now faced the possibility of not being paid on time.

Not to worry — it all came out right in the end, and a new song was even born from it! As I wandered in the woods at the retreat center in Bad Gandersheim, doing hitbodedut about how I was going to survive if the money did not come through, I began to repeat “Uman, Uman — Rosh Hashanah!” over and over like a mantra. Not the usual Breslov tune, just those four words. At some point, it became a chant-like round, which lifted up my heart in joy.

Meanwhile, the conference organizers decided to pass the hat (literally — they used mine!) in order to get me some traveling money. People were very generous, and although it was less money that I had been promised in the beginning, it would be enough to get me by. In return, I taught them my new tune, so now there were Germans, Dutchmen and others walking around singing “Uman, Uman, Rosh Hashanah” to help me on my way.

There was also more practical help. I got a ride from the conference to Berlin, which saved me some train fare, and various friends I had met in Germany from the previous trip provided me with places to stay. In Stuttgart, another group of Germans invited me to lead a discussion about my books, then took up a collection to help with my expenses. So it all worked out for the best.

Rebbe Nachman once said: I have already made it my business to take care of the expenses of those who come to me for Rosh Hashanah (Siach Sarfei Kodesh 1-27). By the time I left Berlin, I had decided that this meant I had to have faith that my day-to-day survival would be taken care of. But on the other hand, I should not expect to make any profit from this trip. After all, a pilgrimage is for God and not for business. With that, I began to live “one day at a time” and leave the rest in Hashem’s hands.

Amazing coincidences…

One rather strange incident gave me a big affirmation that, in spite of all these problems, I was on the right trail after all. When I first arrived in Amsterdam on September 7th, my Dutch host took me to a kosher restaurant called “Carmel.” There we were met by some other people from the Dutch publishing house, along with a man who had read my book and wanted to meet with me privately. Time was tight, so we agreed he would drive me to the next place on my schedule, and we could talk in the car.

On the way, he suddenly decided “on a whim” that he wanted to introduce me to some Russian Jewish friends. So we stopped there — and it turned out they were celebrating their wedding anniversary. I was immediately invited in for some food and a shot of vodka, which I toasted to the family. They asked me where I was from and where I was going, and — here is the amazing part — they were originally from a place near Uman!

Nor was this the only time I met people from Uman. In Stuttgart I spent Shabbat in a hotel next door to the synagogue. There was a bar mitzvah that week, and everyone was invited to the lunch afterward, so of course I stayed. As “coincidence” would have it, I ended up sitting next to a German Jewish man whose wife was a Ukrainian Jew from Uman! She told me to be sure to see the Sophia Park because it was very beautiful (I did and it was — more on that later).

So, although there were financial hassles, there were also reassuring signs which said, “Uman, Uman, Rosh Hashanah!” My determination became stronger then ever to get there, by all means! While on the road, I celebrated the Baal Shem Tov’s birthday with Lubovitchers, went hiking in the Black Forest with a German friend, and sampled a wide variety of beers at the Constatter Folkfest. Then it was on to Paris by train to meet my plane to Kiev.

In Paris, more tests and challenges

Finding the plane was a test in itself, because Charles DeGaulle Airport is really two separate airports, and both are huge. When I left the USA I had confirmation of being on the flight, but the man coordinating the group had forgotten to give me the flight number or even the name of the airline! He then went out of town for a week, and I had visions of myself wandering around the airport looking for other people dressed in Hasidic garb — which might have worked, since we were conspicuous! But after a few frantic faxes and e-mails, I did get the flight information before reaching Paris.

It had been my intent to buy kosher food in Paris to take with me on the trip because, although I am not a fanatic about it, I prefer a vegetarian diet (at home we use no meat or fowl in our kitchen). It has been my experience that most Hasidic gatherings are very meat-oriented, and I was told that vegetables are difficult to obtain in Ukraine. On the road I’ll eat meat to survive, but I much prefer not to. So my plan was to arrive in Paris, go to the kosher shops, and get my own food to take with me.

But when my train arrived in Paris, I discovered that the airport was another 40-minute train ride outside of the city. My flight left at 7:00 AM the next day, which meant being at the airport at 6:00 — too early for taking a train from the city. So I had better find a hotel near the airport. By the time I did that and got checked in, it was already too late to go back into Paris and shop. So there I was, resigned to eating in the meat-oriented dining hall in Uman, or else fasting. But I remembered Rebbe Nachman’s words that, Whether you eat or don’t eat; whether you sleep or don’t sleep; whether you pray or don’t pray — just make sure you are with me for Rosh Hashanah! (Tzaddik #404)

The next morning, I took the hotel shuttle to the airport, only to discover that I had the wrong flight time — the plane did not leave until 9:30, which meant that I could have stayed at a hotel in the city, done my shopping, and had plenty of time to make my connection. So why was I being put through this hassle of going to Uman with no food? There must be some reason for it, I decided…

About an hour later, other Hasidim began to show up at the gate, and when we had a minyan we davened Shacharit (morning prayers). On the same flight was an American Jew named Daniel who now lives near Bordeaux, France. We decided to sit together, since we were apparently the only English-speaking Jews on the plane. It turned out that he was a farmer, so we had a lot in common.

From Kiev to Uman…

Upon arrival in Kiev, there was a long, slow line as we went through passport control and customs. Then a more-than-four-hour-long ride to Uman, in an old red bus that ground its gears every time we went up a hill. At times Daniel and I wondered if the bus was going to make it all the way to Uman without blowing its transmission. But we had a great time looking out the window at the Ukrainian countryside and speculating about what crops were grown there. The land looked rich and fertile, but the agriculture was clearly primitive — in many cases, people were still using horses to haul hay, and drawing water from the well in buckets.

Along the road we also saw people selling everything from potatoes to meat to tires. With the collapse of Communism, the Ukrainians are now free to sell their own goods, but have few ways to market or distribute their produce. A lot of bartering takes place, because nobody has much hard cash. The average Ukrainian, I was told, makes the equivalent of $20-25 per month.

At last, at last — arrival in Uman! When the bus pulled into town, everyone on board suddenly burst into a chorus of “Uman, Uman — Rosh Hashanah!” We were ready to rush joyfully into the streets — but unfortunately, we had to wait more than an hour on the bus while the authorities checked our passports again and carefully wrote down our names. The process was interminably slow, and I thought my bladder was going to burst. I learned later that the organizers of the pilgrimage have to pay a per capita tax to the town of Uman for each Jew who comes — nor was this the only extortion connected with this trip. Everything you might have heard about the Russian Mafia is true and more so. But all that was nothing compared to the joy of having reached my goal — I was finally in UMAN!

To the Rebbe’s grave site

When Daniel and I got off the bus, we were met by Rabbi Chaim Kramer and Ozer Bergman, who both welcomed us heartily and took us to our accommodations, then to the Rebbe’s grave site. Even at that hour — by now it was around 11:00 at night — there was an incredibly high level of activity at the grave. I wish that I could say I had the presence of mind to say “Shehechiyanu” — the prayer which thanks God for having “preserved us, kept us alive, and brought us safely to this time.” But the only thing out of my mouth was, “I can’t believe I’m really here!” which was indeed a prayer of thanks from the depths of my heart! I had finally made it to the “Rebbe’s Zion.”

The Breslover Hasidim now own the land where the grave site is. The Jewish cemetery was destroyed by the Nazis, but a loyal follower named Zavel Lubarski had kept track of the exact location of the grave. He then built a house designed in such a way that the outer wall ran alongside the grave itself. This was covered with an unmarked slab in the back yard. Over the years, the house was constantly occupied by people who knew about the grave and respected it as a holy place. A real miracle!

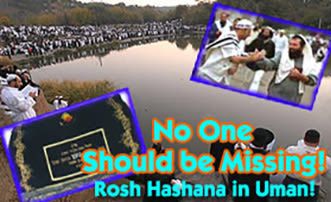

Today there is a large block of granite for a gravestone, covered with an embroidered cloth that is, in turn, covered with plastic to protect it from thousands of hands. There is also a makeshift roof over the area, and benches for sitting to pray or recite the Psalms. Future plans include building a more permanent, dignified structure, along with a synagogue and a mikveh (ritual bath).

An estimated 7000+ Hasidim were there for the pilgrimage (only the Ukrainian police know for sure, since they counted us all) — not only Breslevers, but also Satmars, Belzers, Gerers, plus a lot of Sephardim, Israelis, and Jews of all kinds who were just curious. It was a most incredible mix of dress, ranging from the Satmars in knee-length pants, white stockings, and long black coats, to more “hip” types in blue jeans and sweatshirts, to Yerushalamis in white knitted skullcaps with a tassel on top. Breslov has no “uniform” like some other Hasidic groups, and we pride ourselves on this diversity.

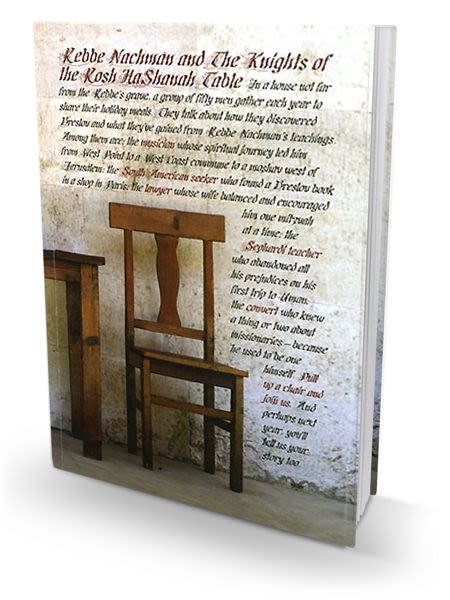

Sharing our stories around the table

As already explained, I had resigned myself to eating in the communal dining hall, but when I asked how to register, Rabbi Kramer invited me to eat at his table instead, to be with the people from Breslov Research Institute. I already knew of Rabbi Kramer through reading his books and a brief correspondence, so I was delighted to accept the invitation. “Aha,” I said to myself, “this is why I was not able to go shopping in Paris.” Had I brought food, I would probably have just eaten on my own. Instead, I found myself sitting at a table in the heart of the English-speaking community, with many opportunities to talk with people who have been Breslevers for decades. Rabbi Kramer himself first made it to Uman during the Communist period — and what a story that was!

It is the custom around Rabbi Kramer’s table for each person to tell how he came to Breslov and how he got to Uman. An amazing set of tales indeed, with Jews from Israel, France, America, South Africa… and, of course, myself from Minnesota. I drank in these stories like a man who had been in the desert for years. Common to them all was the element of personal questing and searching for the Rebbe. A lot of these men had gone to very traditional yeshivot (Jewish religious schools) and were learned in Torah, but something was missing in their Jewish experience — the element of a heartfelt personal relationship with God. This they had found in Breslov.

Rabbi Kramer said that Breslov is different from the other Hasidic groups, where one is usually born into it. A Satmar chassid is a Satmar because his family is Satmar… But most Breslevers actively seek out Breslov, so we come from a lot of different backgrounds. It is, he said, like the cuckoo bird who lays her eggs in other birds’ nests, but when those birds grow up, they seek out and join their own kind. In the same way, the Rebbe’s Hasidim are sometimes born into strange situations, but when they hear the call of the Rebbe’s voice, they know themselves to be Breslevers.

This was certainly the case with me. As I wandered the streets of Uman, I looked back over my life and could see many points along the way when had I encountered Rebbe Nachman’s teachings in the strangest places — but always at just the right time. There was Zalman Schachter’s hippie-style recording of “The Seven Beggars” from the 1970’s, and Gedaliah Fleer’s book, Rebbe Nachman’s Fire which I found about that same time. Then there was the copy of The Divine Conversation by Rabbi Schick, which I found, of all places, at a garage sale in Minneapolis for 25 cents (best quarter I ever spent!) Not to mention many personal mystical experiences with hitbodedut (private prayer), which continued to affirm that I was on the right path.

So, when it came my turn to tell about how I came to Breslov, I said quite truthfully that I’ve been a Breslover for at least two decades, only I had not made connections with the people until the last few years. But the Rebbe’s voice had called me long ago…

Living conditions in Uman

If the spiritual energy in Uman was high, the physical conditions were spartan, to say the least — most of the buildings were not heated, and the weather was quite chilly. There was running water only a couple hours a day sometimes, so we had to fill buckets in case the water gave out. Everything we ate — including drinking water — had to be brought in for purposes of kashrut (Jewish dietary laws), health and safety. Uman is not that far from Chernobyl, so we were not sure about drinking the water there.

Rabbi Kramer had a sign up on the door (for a joke) that said, “Welcome to the Waldorf Astoria.” (His “luxury hotel” actually had heat!) Life in Uman was primitive, but I was prepared for all this by the rural conditions that my wife and I are living under in northern Minnesota. We, too, have had times when the house was chilly and the plumbing did not work. So Uman was not such a big adjustment for me as it was for some of the Jews who had come straight out of the big city.

The climate was about the same as Minnesota for that time of year — cold and drizzly. I was very glad for the layers of warm clothing that I had been “uselessly” dragging with me all over the warmer parts of Europe for the past month. Those heavy black sweatpants and long underwear now came in very handy! So did the gloves, wool jacket, and knitted cap. If you ever decide to go, be prepared to dress warm! The “Minnesota layered look” was definitely in.

The streets in Uman were paved — well, sort of. They were badly in need of repair in some places and, with literally thousands of people tromping around, things got muddy fast. Uman mud is the heavy clay kind that gets all over everything. So I was also very thankful for the pair of Army combat boots I wore!

For most of the year, Uman is just a sleepy little shtetl (country town), so the Breslov “advance team” has a job similar to setting up for Army maneuvers in finding everybody housing, food, etc. At this point in time, only the men make the Rosh Hashanah pilgrimage because of the total lack of privacy, but during the year, many women also go on other occasions. It is hoped that someday there will be hotel accommodations for families to go together, but right now, it is mostly a men’s event. (My wife practically pushed me out the door to go — we Breslevers believe the whole family benefits if even one member makes it to Uman.)

As I said, there are no hotels in Uman (well, actually there is one run-down old hotel left over from the Communist days, which I heard was full of roaches). Many of the local Ukrainians sublet their apartments for the week — the place where I stayed had 10 guys sleeping wall-to-wall on cots, paying about $20 each per night. That adds up to a whole year’s income for the average Ukrainian family. So the Uman locals are glad to have found themselves in the middle of a major “tourist” event, even if it is a bunch of Jews who look like they just walked out of the 19th century.

We were also well-protected by Ukrainian police and soldiers, just to be sure there were no “incidents.” (There had been a terrorist threat against the U.S. Embassy that same week.) I had a chance to try my limited Russian with some of the soldiers, who were just ordinary guys on what they saw as easy duty, guarding these strange Jews who just laughed and danced and made no real trouble.

Saying Psalms at the Rebbe’s Zion

On the morning after I arrived, I went back to the Rebbe’s grave to join in the morning minyan (prayer quorum). Prayers at the grave site were intense and moving. Throughout the Rosh Hashanah gathering, at any time of the day or night, there is a crowd of Jews praying there, so that it is impossible to actually see the gravestone from afar. In order to get close enough to touch it, one must simply push his way in. But there were a few times when the crowd was only two or three people deep, and I was at last able to get to the gravestone itself for my personal prayers.

I gave my charity and said the Ten Psalms — in Hebrew. I had planned to say them in English, because I thought it would be more from the heart in my native language. I had even brought an English version of the Tikkun K’lali (Ten Psalms) with me, but lost it in a train station, along with my prayer-book. In Uman, everything was written in Hebrew because the majority of participants were Israelis. There was not an English copy of Tikkun K’lali to be found at the grave site or anywhere else. (So be forewarned and bring copies of whatever you want to read or study in your own language!)

I was disappointed at first to be unable to read them in English, but then I said to myself, “Look, you know the content of those Psalms, even if your Hebrew is not all that great. You have come all this way to say them here — so why not just say them in Hebrew?”

So I did. And I have continued to say them in Hebrew ever since. That was one of the things which changed for me that Rosh Hashanah. Although I know Hebrew, it is always a struggle for me to read a text out loud because of my dyslexia. I even turn letters around in English — so imagine a dyslexic trying to read a language which goes “backwards!” A definite challenge, to be sure!

Over the years I have gotten very lazy about reading in Hebrew if I have an English text available, because I am embarrassed to be making so many silly mistakes (“What — him a scholar? He can’t even read from the Torah properly…”). But in Uman I finally got over my “Ugly Duckling” complex about my different ways of learning and just accepted myself for who I am.

Walking in Sophia Park

On Wednesday afternoon — the day before Rosh Hashanah — Daniel and I went to the Sophia Park, where Rebbe Nachman used to walk when he lived in Uman (“To be in Uman and not go there???” he once said). It was every bit as beautiful as I had imagined it, although it was rather tame by Minnesota standards. Many of the waterfalls were man-made, and the trails were carefully edged with stones. Still, it was quite lovely, and one could see why Rebbe Nachman identified so deeply with being “the flowing brook, the source of wisdom” (Mishlei 18:4) and why he saw life as “just a narrow bridge.”

Throughout the park, there were Hasidim walking along the trails and climbing or sitting on the rocks for private meditation. Many of the Israelis told me how wonderful it was to see all this greenery, because in Jerusalem, everything is brown and mostly desert. Once again, I was reminded how lucky I am to live in a place where all I have to do is walk out the door to be alone with nature!

My wife Caryl (Rachel), who loves rocks and stones, had asked me to bring her back a small stone from Uman. I had originally thought to take one from somewhere near the grave site, but the reality is, that there was nothing but bits of cement and other man-made material there, because of the new construction. So I found her a stone in Sophia Park instead — which was probably more appropriate anyway, because it was from a natural place where the Rebbe himself might have walked.

Uman, Uman, Rosh Hashanah!

Rosh Hashanah came at last — and what an incredible time it was! Although I had a seat in the big synagogue, I found myself wandering from place to place, saying morning prayers in one minyan and afternoon prayers in another. I experienced a wide variety of styles of davening (worship) as well as solitude when I needed it. I also had many opportunities to talk with Jews from all over the world.

More than once, somebody remarked to me what a miracle it was to be there, and how we might be souls of Breslevers from past centuries who had reincarnated in order to have the mitzvah of traveling to Uman. Looking around at the thousands of men in traditional garb who seemed to just “belong” on the streets of Uman, it was very easy to believe it. I myself had a number of deja-vu moments which made me wonder if I had been there before in another life.

One of the most powerful moments was during Tashlich, when we all went to the river to symbolically “cast our sins into the sea.” In Uman it was absolutely the most incredible Tashlich I have ever experienced — literally thousands of Hasidim pouring down several roads to the river, lining the banks on both sides to say the special Tashlich prayers. Some of the more adventurous souls — including myself — climbed up onto the rocks to say Tashlich from there.

Many Breslover Hasidim wear a kittel (white robe) on Rosh Hashanah as well as on Yom Kippur, and it was a magnificent sight to see so many Jews garbed in white, swaying and praying and dancing along the river banks. Some curious Ukrainians had gathered to watch, and I managed, using my halting Russian and a Ukrainian phrase book, to exchange names and wish peace and freedom to a group of young people. A lot of the Jews were very negative about the Ukrainians, because of the anti-Semitic history of the town. I noticed that the elderly people did not give us much eye contact — after all, they had seen the Nazis take the Jews away, and maybe even helped them do it. But I found the younger generation to be more open and trying to make some kind of human connection with us. My very few words of Ukrainian were appreciated, and smiles went a long way, too.

Immediately after Rosh Hashanah came Shabbat (the Sabbath), when literally thousands of us sang “Lecha Dodi” together, with “ai-ai-ai” between each verse. Then we danced and sang for at least an hour in the makeshift building that served as a synagogue (unheated, but we had plenty of body heat crammed together — and multiple layers of clothing to keep us warm.)

I have never in my life experienced a Shabbat like that! The big synagogue was crammed beyond capacity, and the rest of the people must have gone to other minyans (prayer groups) — the Sephardim tended to have their own services, as did some of the other groups. Still other minyans were at the grave site, etc. There simply was no place where all 7000 of us could gather under one roof.

All too soon Shabbat was over, and Saturday night I began to pack my things to return to Kiev airport in the morning. Daniel and I had not seen anyone from the French group since we had arrived, and we had no idea which bus we were to take, or when it would be leaving. So we literally walked around shouting “Parlez-vous Francais?” until we finally found somebody from the Paris group who told us that the bus would be leaving at 7:00 AM. As it turned out, that information was not accurate either — the bus did not come until 8:00. But at least it seemed to have gotten its gears repaired!

The trip back to the airport was uneventful, and we arrived in time to catch our plane. I slept much of the way back to Paris, having stayed at the Rebbe’s grave until 2 AM the night before. From Paris it was back to Amsterdam for a few more days, and then home to Minnesota. My wife was eager to hear every detail, and I talked her ear off for the entire two hours from the airport to our farm.

The positive effects of the pilgrimage have been many, some obvious and some more subtle. Rabbi Kramer told me in Uman that this experience would change my life forever, and he was right. In a strange way, the Rebbe really did pull me out of Gehenna — many of my personal demons were conquered and thrown into the river along with my sins, never to return. My family and friends have remarked that I seem more centered, more at peace with myself. In addition, I feel even more connected to the Breslov community. Now, as I make hitbodedut (private prayer) along the wooded Minnesota trails in the early morning light, I often find myself dancing and singing, “Uman, Uman, Rosh Hashanah!”

Tell us what you think!

Thank you for your comment!

It will be published after approval by the Editor.