Rabbi Baruch of Medzeboz

Date of Passing: 18-Kislev. Rabbi Baruch of Medzeboz was a grandson of the Baal Shem Tov. He was the first major "rebbe" of the Chassidic movement to hold court in Medzeboz, in his grandfather's hometown and Beis Medrash.

Died: Medzeboz, 1811

Rabbi Baruch of Medzeboz was a grandson of the Baal Shem Tov. Reb Baruch (known in his childhood as Reb Baruch’l, a Yiddish diminutive, and subsequently as Reb Baruch’l HaKadosh) was the first major “rebbe” of the Hasidic movement to hold court in Medzeboz in his grandfather’s hometown and Beis Midrash, which he inherited.

Biography

As recorded in the early Hasidic work Mekor Baruch (first published in 1880 from handwritten manuscripts), at the time of the Baal Shem Tov’s death, Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz and Rabbi Jacob Joseph of Polonoye, two of the Baal Shem Tov’s closest disciples, reported to the Chassidim that the Baal Shem Tov had designated Reb Baruch as his successor, and instructed Reb Pinchas to take responsibility to carry out those wishes. Reb Baruch was only seven at the time of his grandfather’s death, and was raised in Reb Pinchas’ home, where the Baal Shem Tov’s other close disciples and other leaders of the Chassidic movement visited regularly to check on his progress and assist with his preparation to assume his grandfather’s mantle.

Reb Baruch remained with Reb Pinchas of Koretz until the Chevraya Kadisha, as the close inner circle of disciples of the Baal Shem Tov was known, felt that he was ready to become a Rebbe and return to Medzeboz.

Rabbi Baruch was appointed rebbe around 1782. He conducted his court with the principle of malkhuk (royalty). He conducted his court in Tulchyn from 1788 until 1800, after which he moved to Medzeboz. There he built a spacious, luxurious residence where he had a coach and horses in his stable.

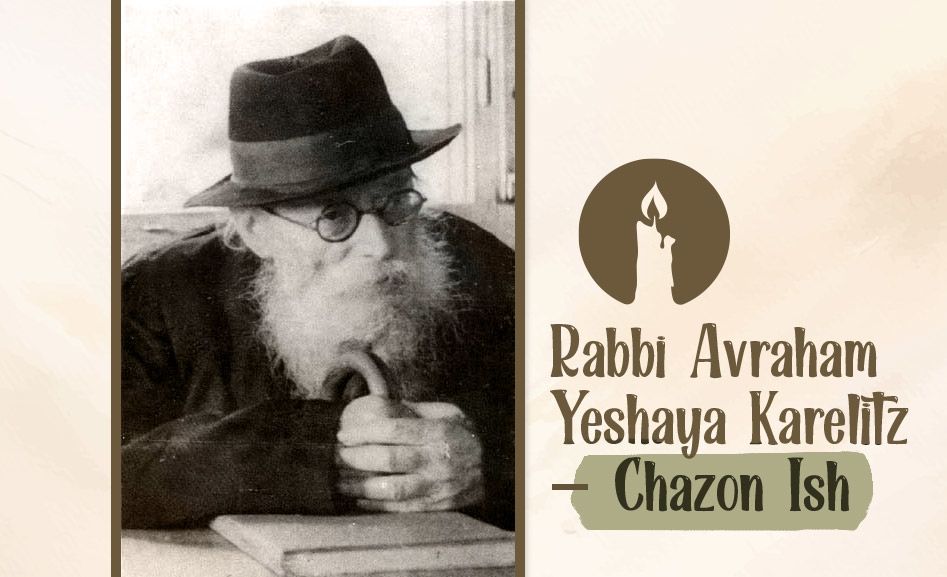

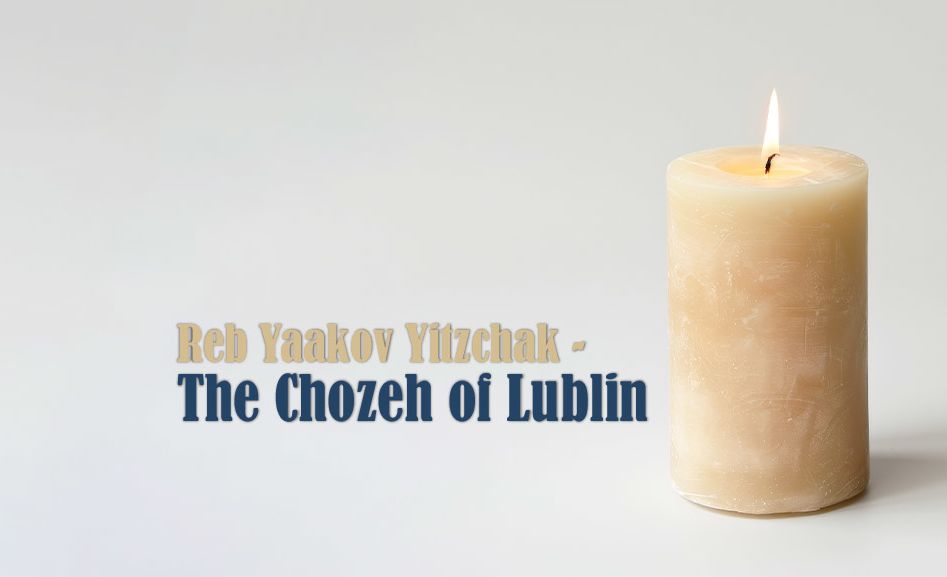

Many of his grandfather’s disciples and the great Chassidic leaders of the time, regularly visited the Rebbe Reb Baruch’l as he was called, including the Magid of Chernobyl, the Magid of Mezritch, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi (founder of the Chabad Hasidic movement), the Chozeh of Lublin, and others.

Reb Baruch was known for his melancholy, fiery temper, and uncompromising strong will. His guiding principle of malkhut was the subject of great debate amongst the Chassidic leadership of his generation. Reb Baruch was the first Chassidic leader to accumulate great wealth from his devotees through the practice of petek and pidyonot. In other words, he obtained donations and gifts for personal requests or prayers. He claimed to his followers that he had supernatural powers derived directly from his blood-connection to the Baal Shem Tov.

In 1808, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Lyadi visited Reb Baruch in Medzeboz to settle their differences. At the time, Reb Baruch was incensed by his [Rabbi Zalman’s] publication Tanya, and by Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s insistence that communal funds be given freely to charitable causes. There are numerous stories related to this visit, most ending with Reb Baruch’s temper getting the best of him. The visit ultimately resulted in Rabbi Shneur Zalman and his followers being evicted from Podolia.

In his later years, Reb Baruch became overwhelmed by his melancholy. In an attempt to remedy his melancholy, his followers brought in Hershel of Ostropol as a court jester of sorts. Hershel was one of the first documented Jewish comics and his exploits are legendary within both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities. One story has it that in a fit of rage, Reb Baruch himself was responsible for Hershel’s death. At least one tale has Hershel lingering for several days and dying in Reb Baruch’s own bed surrounded by Reb Baruch and his followers.

Rabbi Baruch was one of the per-eminent rebbes in the generation of the disciples of the Maggid of Mezritch and had thousands of Chassidim. His brother was the famous tzaddik Rabbi Moshe Chaim Efraim of Sadilkov.

His Torah discourses were written down in Botzinah De’Nehorah (Hebrew).

About Herbs and Healing…

Once he was told in the name of R’ Baruch an explanation of the verse, “. . .he must provide a complete cure, (v’rapoh yirapee)”. He said the (medicinal) herb would provide a cure for the sick man and the sick man would provide a cure for the herb. R’ Sholom Yosef explained.

“When Hashem decrees that a man must undergo suffering, the sufferings are enjoined to strike him at a particular time, and to cease at a particular time by way of a particular person and in response to a particular cure.” (Talmud, Avodah Zara 55a)

Why are a person’s sufferings commanded to act in such a way? It is all for the sake of the herb that has to find it’s Tikkun (healing, rectification) by healing the man. When Adam fell from his lofty spiritual level as a result of eating from the Tree of Knowledge, many sparks were toppled and fell below. Every act of eating or drinking serves to restore these sparks to the place where they belong and thus bring the world ever closer to perfection. How can an herb which is bitter and poisonous find it’s Tikkun? When it is the appropriate cure for a certain ill man and he takes it using the proper intentions, then the Tikkun is effected and the herb has it’s sparks restored. That is what the Sages meant, “by way a of particular person”. It refers to the sick person. As R’ Baruch said, “the ill man heals the herb”.

The Vanished Flame

It was the first night of Chanukah. Outside a snowstorm raged, but inside it was tranquil and warm. The Rebbe, Rabbi Baruch of Medzeboz, grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, stood in front of the menorah, surrounded by a crowd of his Chassidim. He recited the blessings with great devotion, lit the single candle, placed the shammash (“servant candle”) in its designated place, and began to sing HaNerot Halalu. His face radiated holiness and joy; the awed Chassidim stared intently at him.

The flame of the candle was burning strongly. Rebbe and Chassidim sat nearby and sang Maoz Tsur and other Chanukah songs. All of a sudden, the candle began to flicker and leap wildly, even though there wasn’t the slightest breeze in the house. It was as if it were dancing. Or struggling. And then, it disappeared!

It didn’t blow out—there was no smoke, it just was not there anymore. It was as if it flew off somewhere else. The Rebbe himself seemed lost in thought. His attendant went over to re-light the wick, but the Rebbe waved him off. He motioned to the Chassidim to continue singing. Several times, between tunes, the Rebbe spoke words of Torah. The evening passed delightfully, and the Chassidim present had all but forgotten the disappearing Chanukah flame.

It was nearly midnight when the harsh sound of carriage wheels grating on the snow and ice exploded the tranquillity. The door burst open and in came a Chassid who hailed from a distant village. His appearance was shocking. His clothes were ripped and filthy, and his face was puffy and bleeding. And yet, in stark contrast to his physical state, his eyes were sparkling and his features shone with joy.

He sat down at the table, and with all eyes upon him, began to speak excitedly.

“This isn’t the first time I came to Medzeboz by the forest route, and I know the way very well. But there was a terrible snow storm this week, which greatly slowed my advance. I began to worry that I wouldn’t get here in time to be with the Rebbe for the first night of Chanukah. The thought disturbed me so much that I decided not to wait out the storm, but to plod ahead and travel day and night, in the hope that I could reach my destination on time.

“That was a foolish idea, I must admit, but I didn’t realize that until too late. Last night, I ran into a gang of bandits, who were quite pleased to encounter me. They figured if I was out in this weather, at night, alone, I must be a wealthy merchant whose business could not brook delay. They demanded that I surrender to them all of my money.

“I tried to explain, I pleaded with them, but they absolutely refused to believe I had no money. They seized the reins of my horses and leapt on my wagon. They sat themselves on either side of me to keep me under close surveillance, and then drove me and my wagon off to meet their chief to decide my fate.

“While they waited for their chief to arrive, they questioned and cross-examined me in great detail, searched me and the wagon, and beat me, trying to elicit the secret of where I had hidden my money. I had nothing to tell them except the truth, and that they weren’t prepared to accept.

“After hours of this torture, they bound me and threw me, injured and exhausted, into a dark cellar. I was bleeding from the wounds they inflicted, and my whole body ached in pain. I lay there until the evening, when the gang leader came to speak with me.

“I tried to the best of my ability to describe to him the great joy of being in the Rebbe’s presence, and how it was so important to me to get to the Rebbe by the start of the holiday that it was worth it to endanger myself by traveling at night.

“It seems that my words made an impression in him, or else he was persuaded by my insistence even under torture. But whichever it was, thank G-d he released me from the handcuffs, saying:

‘I sense that your faith in G-d is strong and your longing to be with your Rebbe is genuine and intense. Now we shall see if this is the truth. I am going to let you go, but you should know that the way is extremely dangerous. Even the most rugged people never venture into the heart of the forest alone, only in groups, and especially not in a storm and at night. You can leave and try your luck. And I am telling you, if you get through the forest and the other terrible conditions safely, unharmed by the ferocious wild beasts or anything else, then I will break up my gang and reform my ways.

‘If you actually reach the outskirts of the city, then throw your handkerchief into the ditch next to the road, behind the signpost there. One of my men will be waiting, and that is how I will know that you made it.‘

“I then became terrified all over again. The hardships I had already endured were seared into my soul, and now even more frightening nightmares awaited me. But when I thought about how wonderful it is to be with the Rebbe at the menorah lighting, I shook off all my apprehensions and resolved not to delay another moment. My horse and carriage were returned to me and I set off on my way.

“There was total darkness all around. I could hear the cries of the forest animals, and they sounded close. I feared that I was surrounded by a pack of vicious wolves.

“I crouched down over my horse’s neck and spurred him on. He refused to move in the pitch blackness. I lashed him. He didn’t budge.

“I had no idea what to do. At that moment, a small light flickered in front of the carriage. The horse stepped eagerly towards it. The light advanced. The horse followed. All along the way, the wild animals fled from us, as if the tiny dancing flame was driving them away.

“We followed that flame all the way here. I kept my end of the bargain and threw my handkerchief at the designated place. Who knows? Perhaps those cruel bandits will change their ways, all in the merit of that little light.”

It was only then that the Chassidim noticed that the Rebbe’s Chanukah light had returned. There it was, burning in the elaborate menorah, its flame strong and pure as if it had just been lit.

When Reb Baruch died in 1811 on 18 Kislev 5572, his chassidim (followers) numbered in the thousands. He is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Medzeboz, next to his grandfather the Baal Shem Tov. His writings were included in Amarot Tehorot published in 1865 and in Buzino Dinhora published in 1879.

May the merit of the tzaddik Rabbi Baruch of Medzeboz protect us all. Amen

***