A Matter of Life and Death

I walk back into the house noticing my father's empty easy chair and empty place at the dinner table as we attempt to eat with diminished appetites. How little space he took up in the home. How large a space he takes up in my heart.

I walk back into the house noticing my father’s empty easy chair and empty place at the dinner table as we attempt to eat with diminished appetites. How little space he took up in the home. How large a space he takes up in my heart.

The sky is overcast on the day of my father’s death. It is an unusually warm, spring March day in a usual frigid northern Wisconsin climate. An unfamiliar voice on the other end of the phone heralds the dreaded news. “Your father passed away at 10:30 this morning.”

Thoughts of death race through my head. My grandmother used to say, “It’s a good omen when you have nice weather on the day of a funeral.” My mind replays over and over the first line of an Emily Dickinson’s poem I learned as a thirteen year old, twenty-six years earlier, “The hush in the house, the morning after death.”

At the hospital my family and I stand around the shell of what was once my father. Cancer ended his life at the age of 84. He used to tell people in his wry sense of humor that he was half his age, 42 on one side and 42 on the other. “You look good, Abe,” they would say. “I don’t look good, I’m good lookin’,” he always replied, managing to evoke a smile from everyone.

The rabbi rushes into the sterile room where my father’s lifeless body lies, raises his hands above his head in benediction style and offers a quick prayer for the dead. I realize that this is the last time we will be together as a family.

I reflect back to childhood remembering my mother’s words. “When grandfather died, even though I was the youngest, I took care of all the funeral arrangements. Your grandmother was so grief stricken that she practically jumped into the coffin with him.” I knew she was telling me that I would be responsible for my father’s funeral someday.

In the final expression of love my mother stayed up with my father nearly nine straight days in a row at the hospital before he died. Reaching exhaustion, a long time friend kept vigil so that she could grab a quick nap. These last few days have taken a toll on her. She looks so terribly old. Her hair is grayer, and her face is wrinkled and drawn as overcome with grief, sadness invades her body. I know it is now my turn to help with the final arrangements for interment.

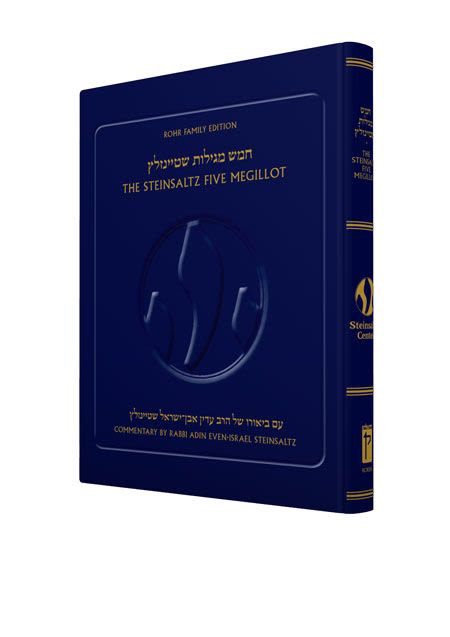

Shrouded in grief I can hardly see as I drive to the funeral home. The shock of my father’s death one hour earlier gnaws at my soul, blurring my vision and dulling my senses. Sitting in the parking lot, I grab the off-white silken prayer shawl and tattered prayer book with splayed binding, no longer serving its purpose, to be buried with my father. Leafing through the book I take one last look at the treasures so dear to him as tears rain on the pages.

I visualize my father untiringly wrapping the tefillin – small leather boxes containing quotations from the Hebrew scriptures – around his arm and forehead every morning and at night praying from this worn book with a subtle smile on his face suggesting gratitude for a blessed life. He probably didn’t need the prayer book. He seemed to know the Hebrew contents by heart.

Carefully, I comb through each page in hopes of finding a remnant of his spirited life. Nestled neatly in the black holy book I am surprised to find a blue and silver foiled Chanukah dreidel (spinning top) decoration my father used as a bookmark. I realize how playful he was in choosing the dreidel to keep his place in a sacred prayer book. Weeping silently, I carefully remove the treasure knowing that my mother will appreciate this last memento. I hug the limp prayer shawl close to my heart inhaling the lingering trace of my father’s scent. My body shakes as I explode into uncontrollable sobs.

Regaining my composure and gathering my courage, I step inside the funeral home and drop the prayer book and prayer shawl off. Later I return with my sister to choose a coffin. There is only one choice, a plain wooden casket with a Star of David carved on top. According to the Talmud, the collection of ancient rabbinical writings that make up the basis of the Jewish religion, simplicity, uniformity and equality are important.

Elaborate burials are frowned upon. The Talmud believes a funeral is no place to flaunt wealth. It is customary to be buried in a wooden coffin without ornamentation. Additionally, wood allows the body to naturally decompose, enabling the soul to ascend to heaven.

My sister and I continue the funeral arrangements and supply information for the obituary. I call relatives telling them the sad news, asking some to be pallbearers. All offer condolences and are willing to help.

After the funeral in customary fashion, relatives and friends gather to console the grieving family. Friends prepare a meal freeing the mourners of food preparation responsibilities in their time of grief. My mother asks, “Please make sure the yard looks presentable for our visitors after the funeral.”

I begin clearing branches from the lawn. The sky grows grayer as the day progresses. It starts to sprinkle. I recall my sister’s stormy wedding day fifteen years earlier, my father joking, “I hope this rain keeps up, so it won’t come down.” I pick up another branch and notice the neighbor’s dog has left his droppings. Scooping it up I think, this is probably the highlight of my day. Why am I joking now at the saddest time of my life? I realize that when faced with the most tragic situations, God grants the inner strength necessary to carry on. I also realize that I am making light of a serious situation, exactly as my father would do.

I walk back into the house noticing my father’s empty easy chair and empty place at the dinner table as we attempt to eat with diminished appetites. How little space he took up in the home. How large a space he takes up in my heart.

Readying ourselves for the funeral my mother instructs, “Put glasses of water in front of the house for our guests to wash their hands.”

“Why do we do this?” I ask.

“It’s a symbolic gesture so that God will wash away the tears of the mourners,” she replies.

The ride in the hearse is silent and painfully long, even though it is only a few miles to the cemetery. We drive from the funeral home, past the synagogue one last time in a gesture of farewell, and then out to the grave site.

The mourners clad in black, standing on soggy earth, gather around the waiting grave. With creaking sounds, the casket is slowly lowered into the ground. More prayers. One by one the mourners place a shovelful of earth on the coffin. Tradition considers this participation in the funeral a mitzvah, one of the greatest deeds of kindness, because the recipient is unaware of the deed, and the deed cannot be repaid. The sound of the earth dropping on the casket, further, helps mourners accept the reality of death and promotes the healing process.

The Kaddish, a prayer to help the soul pass to heaven, is chanted, bringing the mourners from despair to a place of life and hope. There is no mention of death in this prayer. It is a request for peace, exhalting and honoring God.

With a saddened heart I look up and through the hushed silence of death, the sun quietly appears, gracing my father’s final resting place with a prism of light. The heaviness in my heart lifts for a brief moment. It’s a good omen when you have nice weather on the day of a funeral.

As years pass, I discover that death does not separate the bond of love so deeply rooted in the heart. On the anniversary of my father’s death, according to the Jewish calendar, I light a candle in his memory. This traditional Jewish practice signifies the spirit and soul of the departed. The candle burns for twenty-four hours. It comforts me.

Lynda is a friend of mine. Her mother died many years ago. On Mother’s Day to ease the pain she sends a card to her aunt, something she has never done before. She feels this keeps her connected to her mother and is as close to a mother-daughter tie as she can get. To honor her father’s memory each year, Myrna, another friend, shares “dad” stories with her family, attends the state fair, something he enjoyed doing, or eats his favorite candy, chocolate covered orange slices, in celebration of his life and birthday.

I now understand that my father is still with me in his physical attributes that remain in every cell of my body from my tall frame to my long fingers. I see his fingers when I look at my hands. He is still here with rich stories that will be recalled and handed down to the family. He is here in the strength that he mirrored during trying times. When forced with difficult decisions I quiet myself and ask, how would Dad have handled this situation? He remains my gentle guide.

Although he is not physically with me, I feel his presence all around in my thoughts and deeds. I realize that my father and I are united in spirit, and that death will not sever our love; it will only make it stronger. The lovely Jewish traditions that guide my father to heaven, ease the pain of his passing and grace me with the gift of renewed hope for a bright future.

4/11/2023

terrific